News

Kunisada and the Tattoos of Kabuki Theatre

Posted On: 02 Aug 2021 to Tattoo Prints, Japanese Woodblock Prints, EducationThe history of tattoo culture in Japan amongst the kabuki actors portraying otokodate in Edo period plays. Originally published in Tattoo Life Magazine, Jan – Feb 2020

.jpg)

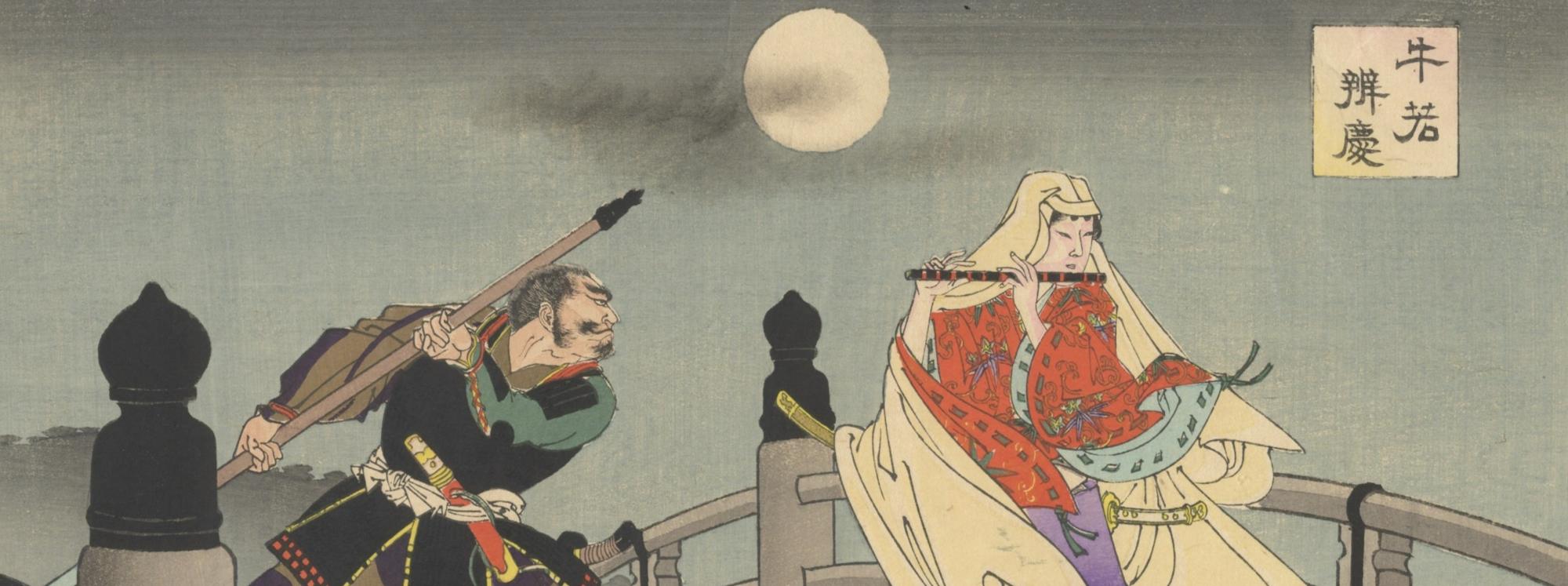

The urban culture that developed in Edo city (today’s Tokyo) in the 18th and 19th century was a pleasure seeking one as townspeople saw kabuki theatre as the ultimate entertainment. Kabuki and its lively and daring performances offered a break amid a restricted lifestyle with plays largely inspired by everyday sensational events. Actors were the real stars of the day, just like today’s movie or pop stars, and their fame reached such heights that woodblock prints depicting actors in their roles became collectibles and souvenirs for the fans. Kabuki also became a medium for tattoos with many popular roles having tattooed heroes and ruffians with flamboyant costumes and extravagant poses.

Omatsuri Kingoro and Kakuno Kosan, 1858

Kunisada Utagawa (1786-1865) stands as one of the most recognised artists that designed woodblock prints centred on the colourful world of kabuki. Passionate about the art form from a young age, he was accepted as an apprentice around 1800 by one of the great masters of the Japanese woodblock print, Toyokuni I (1769 – 1825), and became one of his chief pupils. In keeping with a tradition of Japanese master-apprentice relations, Kunisada’s talent and popularity would lead him to be honored with his master’s name and become the head of the Utagawa art school himself.

Life for everyday people in Kunisada’s time was strictly controlled by corrupt authorities and there was little leeway to express themselves freely. However, a new group began to distinguish themselves and challenge the injustice faced by commoners – the otokodate. Roughly translated as ‘street knights’, their confidence and bravery made them popular among the merchants, clerks, shopkeepers, and artisans who would often rely on them for protection against injustice. In this way, the samurai and otokodate were natural rivals, and as each group banded together into teams under leaders, fierce and bloody clashes broke out frequently.

Ichikawa Ichizo III as Nozarashi Gosuke, 1858

The otokodate were one of the main groups to adopt tattoos as a recognisable feature in tune with their fearless personalities and were so idealised and romanticised by common people that they became part of ukiyo-e and kabuki dramas. In this political environment, Kunisada often depicted actors in imagined settings and resembled their personalities to great heroes that ordinary people would praise and root for when they were performed on stage. The actors often showcased striking tattoos on their bodies, capturing to a great degree a sense of social decay and public discontent, making them, like the dramas they represent, quite modern in their questioning of established values. It is no wonder that from time to time the government of the time found it necessary to censor a theatre that seemed to call into question its authority.

An iconic kabuki play that was often the subject of woodblock prints was ‘Summer Festival: Mirror of Naniwa’, focusing on an exciting character named Danshichi Kurobei, a fish seller by trade and an otokodate. This powerful drama revolves around Danshichi’s loyalty to his former master Tamashima, the strong bond he shares with his friends and his fatal relationship with his vicious father-in-law, Giheiji. The first act culminates with a scene in which Danshichi, tries to retrieve the courtesan-lover of Tamashima’s son from Giheiji who has abducted her out of revenge. The performance ends in a thrilling fighting scene in which Danshichi, unable to reason and enraged by Giheiji, chases and kills the wretched, mud-drenched old man. Stripping to reveal his magnificently tattooed back and limbs, Danshichi strikes heroic poses while stabbing Giheiji to the sound of the festive drums in the background. Danshichi takes the old man’s life with a thrust of his sword, then washes splattered blood and Giheiji’s muddy hand prints from his body, using water from a nearby well. He escapes by mingling with the large crowd of festival celebrants. In stage performances during Japan’s hot summers, the use of real mud and real water would have given the audience a pleasant feeling of coolness, but also the satisfaction that justice had been done on their behalf.

Kunisada’s rendition of an actor in the role of Danshichi shows him bearing a lobster tattoo on his forearm, a reference to the character being a fishmonger, but also a symbol of strength and protection. On his shoulder and chest are the feathers of a phoenix. Unlike the western counterpart, the phoenix in eastern mythology is said to appear only in times of peace and prosperity. It is also said that the phoenix is a creature of morality, shunning those who do not meet its high moral standards, it does not tolerate abuse of power and stands for justice and graciousness.

Ichikawa Kodanji IV as Danshichi Kurobei, 1859

Played by handsome actors, the otokodate became a focus of romantic desire. These warriors were viewed as folk heroes and seeing them in prints or on stage inspired fans to get tattoos of the same imagery that their fictional role models had tattooed on their bodies. Eventually, the same engravers who once created woodblocks took their craft to a new medium – human skin. Ukiyo-e and traditional Japanese tattoos are so intertwined that the word for hand-poked tattoos, tebori, a technique that is still practiced today, means ‘to carve by hand’.

Kunisada’s world was there to be enjoyed. He gave his audience an escape from the restrictions of their ordinary lives, and his images, with their optimism and verve, still have the capacity today to attract and entertain. Whether through kabuki theatre or the production of powerful images in ukiyo-e or tattoos, these art forms were crucial in creating myths central to Japanese history, reflecting both the ideals and dreams of the people.

Text: Geanina Spinu

Originally published in Tattoo Life Magazine, Jan – Feb 2020